Expert Units in Conditioning Large Language Models

LLMs acquire a vast amount of information from pre-training data. However, the mechanisms by which LLMs store this information remain unclear.

In this page, I will review the paper “Self-conditioning Pre-Trained Language Models” published in ICML 2022. The authors of this paper focus on the conditioning generation of LLMs. They propose a method to identify expert units that can effectively condition the generation of LLMs. Surprisingly, these expert units constitute only a small fraction of the LLMs, yet they can condition the generation of LLMs effectively. This discovery provides a deeper understanding of how LLMs can store and utilize information efficiently, highlighting the potential for more targeted and effective conditioning in future models.

Paper Review: “Self-conditioning Pre-Trained Language Models”

Background

TLMs and Conditioning

Transformers have achieved remarkable success in various NLP tasks, thanks to their ability to capture complex patterns in text data. Since its development, the transformer architecture has been widely adopted in various pre-trained language models (TLMs), such as BERT, GPT, and RoBERTa.

Despite their success, the underlying mechanisms that enable TLMs to condition text generation are not yet fully understood. TLMs have two important drawbacks:

Conditioning their generation requires either expensive fine-tuning or the use of additional parameters.

For example, (Chen et al. 2019) employ two latent embeddings for syntax and semantics, enabling flexible conditioning. (Romanov et al. 2019) utilize adversarial training to separate meaning and format. These methods often necessitate pre-known conditioning, substantial data, and complex computations.

TLMs might inherit and perpetuate biases present in the training data.

TLMs are trained on large-scale datasets, which may contain biases that are inadvertently learned by the model. For example, sexism, racism, and other forms of discrimination have been observed in TLMs. These biases can be harmful when the models are used in real-world applications.

Expert Units

To address these issues, the authors focus on expert units.

The concept of expert units has been previously explored in the image domain, where these units are neurons that specialize in recognizing specific objects or patterns. To adapt this concept to NLP, it is necessary to redefine what expert units are, how to identify them, and how to utilize them effectively.

(Radford et al. 2019) identified an expert unit for sentiment in LSTM representations using L1 regularization of a logistic regression classifier on top of the representations. Building on this work, the authors of the reviewed paper aim to use expert units to condition the generation of TLMs. However, (Radford et al. 2019)’s method is limited to sentiment and small-scale models.

Therefore, the authors have developed a new method to identify expert units that can effectively condition the generation of large-scale TLMs.

Difinition

For clarity, the authors first define Conditioning.

In this paper, Conditioning refers to the process of guiding text generation to adhere to a specific concept.

The authors review the approach by (Kim et al. 2018) and extend it to the NLP domain by describing a concept $c$ with a dataset $\left(\mathbf{x}^c_i, b^c_i \right)^N_{i=1}$ consisting of $N=N^+ + N^-$ sentences. The $N^+$ positive sentences contain the concept $c$ (i.e., $b^c_i = 1$), while the $N^-$ negative sentences do not contain the concept $c$ (i.e., $b^c_i = 0$). Each sentence $x^c_i$ is padded to a length $T$.

Method

Interpreting Conditional Generation

Auto-regressive language models generate text by sampling from a conditional distribution over the next token given the previous tokens. More formally, the models maximize the probability of a sentence $\mathbf{x}$ as $p(\mathbf{x}) = \prod_{t=1}^{T} p(x_t | x_{<t})$.

In previous work, interpretation of the conditioning generation was based on the joint probability of the sentence and the concept as $p(\mathbf{x}, y) = p(y\mid \mathbf{x})p(\mathbf{x})$, where $y$ is the conditional variable. However, rather than jointly sampling $\mathbf{x}$ and $y$, the authors set the condition $y=c$ beforehand, thus:

\[\begin{equation} p(\mathbf{x} \mid y=c) \propto p(y=c \mid \mathbf{x})p(\mathbf{x}) ~~~~~~~~~~~ (1) \end{equation}\]Unlike implementing the model $p(y=c\mid \mathbf{x})$ with external networks, the authors hypothesize that the internal generative mechanism of the language model exploits $p(y=c\mid \mathbf{x})$ that already exists within the model. Therefore, the model naturally obeys a factorized conditional generation and is able to maximize $p(\mathbf{x} \mid y=c)$ by exploiting its internal structure.

Conditioning with Expert Units

The authors denote as expert units those neurons that contribute to the conditional model $p(y=c\mid \mathbf{x})$ in (1).

To identify expert units, the authors propose a method that consists of three steps:

- Obtain the output $\mathbf z_m^c=\left(z_{m,i}^c\right)^N_{i=1}$ for each neuron $m$ in response to sentences $\left(\mathbf x_i^c\right)^N_{i=1}$.

- Measure the average precision ($AP_m^c$) of unit $m$ for the task $\mathbf b^c=\left(b_i^c\right)^N_{i=1}$, so that $AP_m^c=AP(\mathbf z_m^c, \mathbf b^c)$.

- Select the top $k$ units with the highest $AP_m^c$ as expert units.

Then, the authors define the intervention on top-k expert units as a $do(c,k)$ operation. This operation involves manipulating the activations of the identified expert units to condition the model’s output. Let $\mathcal Q_k$ be the indices of the top-k expert units. The intervention is then defined as:

\[\begin{equation} do(c,k) : \left(\mathbf z_m^c := E_{x^c}[\mathbf z_m^c \mid \mathbf b^c=1]\right)_{m\in \mathcal Q_k} ~~~~~~~~~~~ (2) \end{equation}\]By applying the intervention $do(c,k)$, the conditional probability $p(y=c\mid \mathbf{x})$ as described in equation (1) is maximized. This ensures that the model’s output is effectively conditioned on the concept $c$. Importantly, the overall probability distribution $p(\mathbf{x})$ remains largely unaffected because the number of expert units $k$ is significantly smaller than the total number of neurons $M$ in the model.

Experiments

In their experiments, the authors evaluate in two points:

- Conditioning Effectiveness

- Bias Mitigation

Conditioning Effectiveness

In first analysis, the authors show qualitative results of the conditioning using the GPT-2 model. The dataset consists $N^-_c\leq 1000$ and $N^+_c\leq 1000$ sentences for each concept $c$. By using this dataset, the authors measure $AP_m^c$ for each neuron $m$ and select the top-k expert units for each concept $c$.

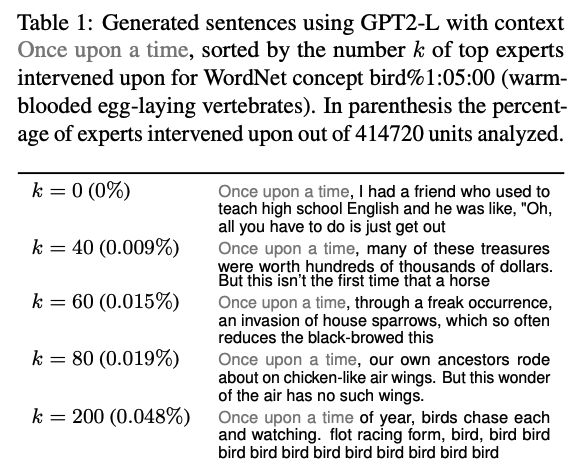

Table 1 presents the inference results of the GPT-2 model when applying the intervention $do(c,k)$, comparing different values of $k$.

As shown in Table 1, the intervention $do(c,k)$ significantly enhances the model’s ability to generate sentences conditioned on the concept $c$. However, as the number of expert units $k$ increases, the marginal gains in performance begin to decrease.

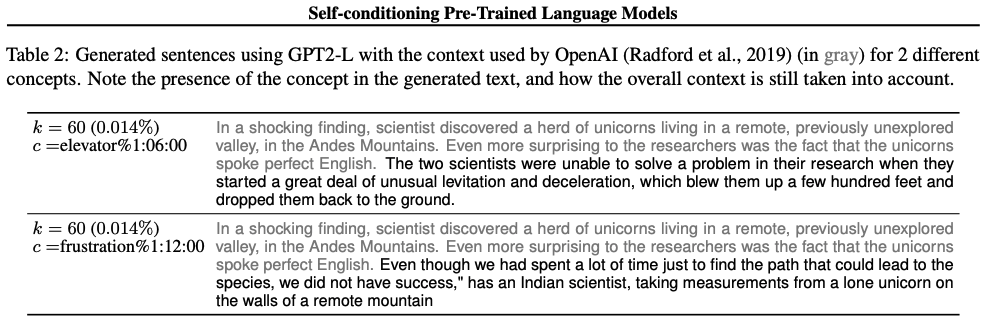

Table 2 presents the results of the intervention $do(c,k)$ for different concepts $c$.

The results in Table 2 demonstrate that the intervention $do(c,k)$ is effective across a wide range of concepts, highlighting the versatility of the proposed method.

Bias Mitigation

In the second analysis, the authors assess the role of expert units in reducing biases within the GPT-2 model. They specifically examine the likelihood of generating the pronouns “he” and “she” in various contexts. For clarity, the authors denote $p(he)$ and $p(she)$ as the probabilities of generating the words “he” and “she,” respectively.

Additionally, the authors introduce the difference in probability $\Delta p(c,*) = p(* \mid c) - p(*)$ as a measure of bias. The placeholder $*$ refers to hyperparameters such as $k$ depending on the method. Parity is achieved at the parity point $\Delta p(c, \star) = 0$, which is the intervention level $\star$ where the model generates “he” and “she” with equal probability.

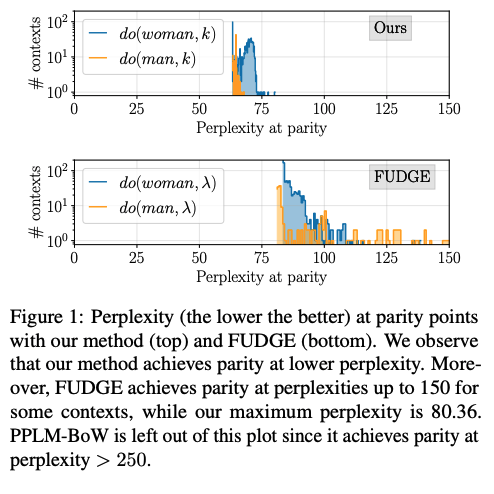

Figure 1 report the perplexity at the parity point measured on the conditioned text generated by our method and FUDGE.

The results in Figure 1 show that the proposed method reduces biases without significantly affecting the overall perplexity of the model. In contrast, the FUDGE method, which uses a separate network to condition the model, results in a higher perplexity at the parity point. This suggests that the proposed method is more effective at mitigating biases while maintaining the model’s overall performance.

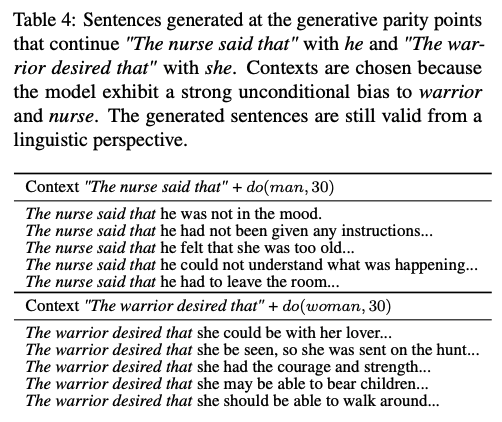

Table 4 presents the results of the intervention $do(he,k)$ for the sentence “The nurse said that” and $do(she,k)$ for the sentence “The warrior desired that”.

The results in Table 4 demonstrate that the proposed method effectively conditions the model to generate “he” and “she” in the desired contexts, reducing biases in the model’s output.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the authors propose a novel method to identify expert units that can effectively condition the generation of large-scale TLMs. By leveraging these expert units, the authors demonstrate that the model can be conditioned on specific concepts without the need for additional parameters or complex computations. The proposed method is effective across a wide range of concepts and can mitigate biases present in the model’s output. This work provides valuable insights into the mechanisms by which TLMs store and utilize information, paving the way for more targeted and effective conditioning in future models.

References

Chen, M., Tang, Q., Wiseman, S., and Gimpel, K. A multitask approach for disentangling syntax and semantics in sentence representations. NAACL, 2019.

Romanov, A., Rumshisky, A., Rogers, A., and Donahue, D. Adversarial decomposition of text representation. NAACL, 2019.

Radford, A., Wu, J., Child, R., Luan, D., Amodei, D., and Sutskever, I. Language models are unsupervised multitask learners. arXiv preprint, 2019.

Kim, B., Wattenberg, M., Gilmer, J., Cai, C., Wexler, J., Viegas, F., and Sayres, R. Interpretability beyond feature attribution: Quantitative testing with concept activation vectors (tcav), 2018.